A recent article delves into the historical roots of Mad Studies, shedding light on the enduring legacy of individuals who critiqued traditional psychiatric and psychological narratives long before the field was formally recognized.

Mad Studies, a field dedicated to challenging traditional psychiatric narratives, has roots that stretch back centuries. Geoffrey Reaume’s new article in Qualitative Inquiry unearths these origins, showcasing the written accounts and activism of mad individuals from the 15th to early 20th centuries, who laid the groundwork for today’s critical perspectives on mental health.

“Mad Studies belongs to all those people who are mentioned here and countless others whose critiques have populated this history since the initial first-person accounts of madness began. That includes voices unknown today but who spoke up at some point in their own lifetimes but have been silenced forever by the passage of time. Yet, their cumulative efforts, known and unknown, continue to have an impact,” writes Reaume.

Reaume’s article paints a comprehensive picture of the rich, yet often overlooked history of Mad Studies. It reveals how mad individuals have long critiqued and resisted dominant psychiatric models through their writings and activism. These early efforts, dating back to the 15th century, provide a critical lens through which we can reexamine current mental health practices.

Reaume’s article, “The Qualitative Historical Origins of Mad Studies in Word and Deed, 1436–1914,” delves into the deep historical roots of Mad Studies.

Reaume’s article, “The Qualitative Historical Origins of Mad Studies in Word and Deed, 1436–1914,” delves into the deep historical roots of Mad Studies.

The origins of Mad Studies are built on centuries of work by people who critically interpreted their own experiences and those of others. While many early writers did not identify as “mad,” their accounts challenged the prevailing religious and medical models that dominated Western culture. Reaume points out that many writings from this period were lost for centuries and are still waiting to be rediscovered.

Historical accounts of mad people were predominantly authored by white upper- and middle-class individuals or observers with the literacy and means to document mad experiences. These early writers were the first to record the experiences of mad people, laying the foundation for what we now call Mad Studies. Despite their limitations, these authors provided critical insights into the mistreatment and social prejudices faced by mad individuals.

Reaume traces historical accounts from 1436 to the early 1700s, revealing how mad individuals often framed their experiences within religious narratives. For instance, Margery Kempe’s recollections mix religious imagery with her personal struggles, reflecting the era’s deeply entrenched religious beliefs and patriarchal structures.

“While the devil is largely blamed for her madness, which is equated as badness, the point of Margery’s recollection is a sort of self-blame for causing her mental distress due to doubting God, and so she was punished by thoughts which drove her to such despair,” notes Reaume.

Historians and Mad Studies supporters emphasize the authenticity of first-person accounts. These narratives often include reflections on self-hatred, suicide attempts, and other forms of self-harm, highlighting the complex interplay between personal experiences and social rejection. Recovery stories frequently credit the support of loved ones for the individuals’ gradual return to mental stability.

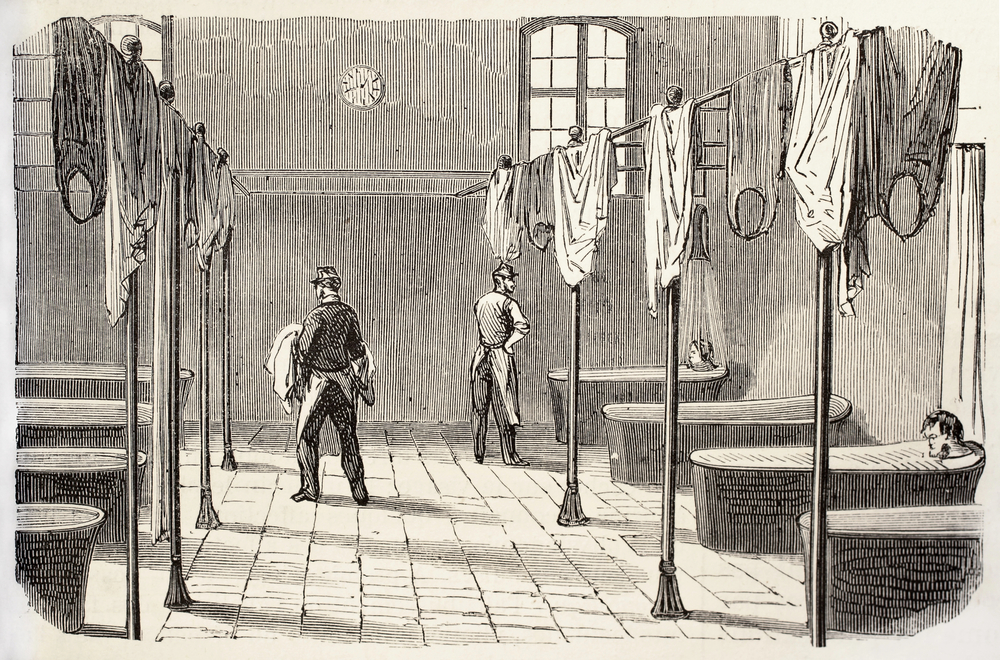

Between the 1700s and 1914, numerous accounts of forced confinement in madhouses and asylums emerged. These narratives formed the basis of public awareness and protest literature. The documented history mainly comes from privileged individuals who had the social capital and skills to articulate their experiences. Despite the predominance of white, able-bodied voices, these accounts provide valuable insights into the systemic abuse faced by all mad people.

Educated men like Alexander Cruden (1699-1770) detailed their abusive confinement experiences, often framing their accounts as critiques of the unjust systems that detained them. Cruden’s accounts are among the earliest records of restraint in confinement, describing his forced feeding “like a Dog” and other forms of violence.

William Belcher, who was confined for 17 years, linked madness and disability, a crucial connection later expanded by Mad Studies scholars. Belcher believed he was not mad at the time of his confinement but became mad due to the abusive conditions.

In the 19th century, writer-activists like Elizabeth Packard emerged, challenging the patriarchal norms that confined women to asylums. These activists argued that madness was often criminalized and pathologized, further marginalizing mad individuals. However, some activists demonstrated insensitivity, failing to acknowledge the compounded social impacts on Black slaves at the time.

While Mad Studies is a relatively new academic field, its historical roots are deeply embedded in the centuries-old accounts and activism of mad individuals. These historical writings provide critical evidence of how mad people have always analyzed their own experiences and resisted dominant narratives. By understanding this rich history, we can better appreciate the complexities of mental health and continue to challenge the ongoing influence of religion, race, privilege, and culture in the treatment of mad people.

Reaume’s article underscores the importance of recognizing the historical roots of Mad Studies. The field owes much to the early writers and activists who documented their experiences and challenged the dominant psychiatric models. By highlighting these voices, we can continue to push for a more inclusive, rights-based approach to mental health care that values lived experiences and diverse cultural contexts.

“What madness means, to whom it applies, and why, has always been a highly controversial issue for those to whom this term has impacted most directly. Mad Studies is thus old and new thanks to those whose efforts have provided centuries of critique and analyses of what it means to be mad in the societies in which they have lived,” concludes Reaume.

****

Reaume, G. (2024). The qualitative historical origins of mad studies in word and deed, 1436–1914. Qualitative Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004241253249 (Link)