I‘d never felt claustrophobic until those triple-locked doors slammed shut. For the first time in my life, my movement was restricted. My freedom was curtailed, and I had to abide by someone else’s schedule.

This wasn’t prison, although it felt like it. This was a mental hospital — my new home.

The most desperate year

By 2010, I’d been depressed for three years without respite. I’d been medically retired from my job as a police officer due to PTSD. My identity, hopes, dreams, and friends had been wrenched from me, and I was falling into the abyss. I had no focus, and every breath hurt.

I’d thought about suicide every day, but until 2010, it was a daydream. In 2010, I felt a serious pull to take action. I’d worked out how, when, and where.

My final straw came when I went to Scotland on our annual family vacation. My dad worked himself to death all year for this two-week break. He loved the isolation and the long walks. Usually, we would mess around in a nearby river and play games in the garden. At night, I’d beat him at golf on the PlayStation.

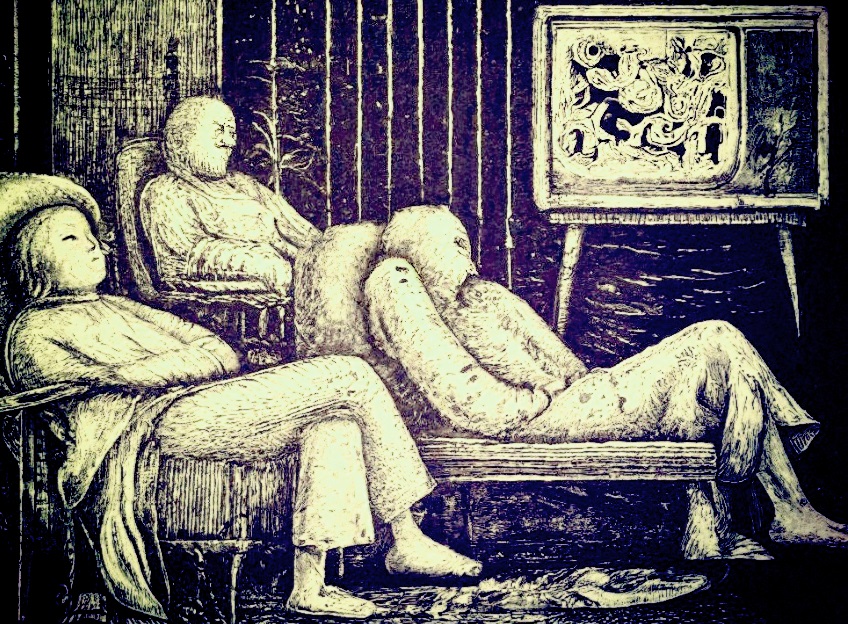

2010 was different. The depressive weight that was crushing my chest 24/7 felt even heavier. I was in a place I knew I was supposed to love, with so many fond memories, yet I felt no joy. There are some photos of me lying on the sofa, which my dad took (he liked to take pictures unannounced for a laugh). The pain is etched on my face.

My family saw how much pain I was in, and they decided to cut the vacation short to get me home and see my psychiatrist. When I heard this, I hugged my dad, and he stifled tears. He could feel my pain.

Due to ill health, that was my dad’s last vacation. However you dress it up, I ruined it for him. The guilt is powerful to this day.

The hospital of last resort

I had run out of options. Medication wasn’t working, and I was too psychotic for therapy. I’d ruined my dad’s vacation, and I was planning my suicide every day.

I was being visited by the Crisis Intervention Team every day. I finally admitted to them my suicidal plans. They said I needed to go to hospital as an inpatient. I went voluntarily so that they didn’t have to section me under the Mental Health Act.

Saying goodbye to my family was crushing. I told my partner they thought I’d be gone for at least several weeks. She broke down crying. As I walked into the living room, my dad immediately began crying, and we embraced. My mum then drove me on the most terrifying journey of my life.

I’d left behind all the love I had in the world for the unknown. All my security surrendered because I couldn’t live like this a moment longer.

My mum stayed with me while a nurse showed me around the hospital. It didn’t take long — my room, a TV room, and a kitchen. I was allowed to keep my phone, but not the charger to keep it running.

We said goodbye, and three double-locked doors closed behind her. With no phone, I’d never felt as alone. The claustrophobia was overpowering. There was no outside space, so we were allowed to pace up and down the corridor or watch TV. I started to realize I’d made a big mistake.

If you stay in a mental hospital, you’d better like TV

Sometimes I see TikToks from angsty teens who treat mental hospitals like a second home. They show these bright and breezy environments with friendly staff and productive activities. They stop wanting to hurt themselves because they’ve made a bowl and spoon that day. Everyone comments on their bravery, and they get thousands of likes.

My experience was nothing like that.

The routine here was simple. At 6 am, the nurses wake you and kick you out of your room. You aren’t allowed back there until 11 pm.

The patients are then all assembled in the “TV room.” A nurse watches over them. It’s the most straightforward job because we are all in one place. The other nurses are behind the scenes, stuffing their faces with cookies. The one nurse watching us rotates throughout the day.

In the TV room, we can sleep as much as we like or watch TV. That’s it — that’s the extent of our activities in this vile place. We can’t sleep in bed because that would be too much work for the nurses to watch us.

The TV was constantly on MTV. I grew to hate The Wanted singing, “How do you get up from an all-time low?” I wish they’d told me the answer.

At 11 pm, they herded us all off to bed. I first noticed the thin plastic mattresses were the same as those I had given prisoners. I already felt like I was in prison. Everything had reversed.

The nurse’s station was down the corridor from my room. The doors had to be left unlocked so anyone could walk in anywhere. I struggled to sleep from the noise of the nurses laughing, shouting, and joking.

They were a bunch of insensitive pigs.

I had no idea what the other patients were like, so I hardly slept in case one came through my unlocked door.

Then, at 6 am, they forced us back into the TV room to repeat the sorry process. The only variation was whether I wanted tuna or beans on my rock-hard jacket potato.

From the frequent fliers to the depths of despair

Most of the patients were frequent fliers. They seemed content to go there for a few days and get discharged, only to repeat the pointless process.

Loving mental hospitals might be a mental illness in its own right.

Yet, among the people who liked tuna and hard potatoes were some tragic cases.

One woman was so overwhelmed by postpartum depression that she curled up in a ball in the TV room. She slept until the nurses allowed her back to bed. Her husband visited often, but she shunned him. She couldn’t bear to be near him. She blamed him for her condition, which I can understand. The most humane thing would have been for the nurses to let her sleep in her bed instead of on a plastic chair.

In mental hospitals, convenience for the staff takes precedence over humanity.

Another patient became progressively agitated at the inability to go anywhere. His only crime was being ill. The situation climaxed when he snapped and started struggling with the windows. The nurses restrained him until he ran out of energy. I don’t know what happened to him, but I imagine he realized no help was available. We were just killing time in the waiting room of the wretched.

The great escape

I lasted a few days before I had to plan how to get out of this nightmare. It turns out the solution was easy because no one cared anyway. I finally got to see a psychiatrist after three days. I told him I felt fine now. The nurse who showed me around objected and asked how I had gone from suicidal to fine in such a short time. But the psychiatrist didn’t care. He needed the bed, so he discharged me.

In a way, the hospital had made me feel better. It had shown me a vision of hell that was going to become my future if I didn’t take drastic action. Getting out of there started my road to recovery. I had everything I needed with my family. Professionals were, and have always been, useless in helping me.

Some people need treatment as inpatients, especially if they’re a danger to others. However, that treatment has to consist of more than sitting in front of MTV for 17 hours a day. It must be more humane than ruining sleep and doing the bare minimum.

Mental health services in the UK — and I suspect elsewhere — have always been in crisis. I don’t know the solution, but humanity from the professionals responsible for helping us would be a good start.