Did Something Happen?! The Power of Poetry in Telling My Son’s Story

Me: I think there’s a lot of trauma he has to process

Dr. K: Did something happen?!

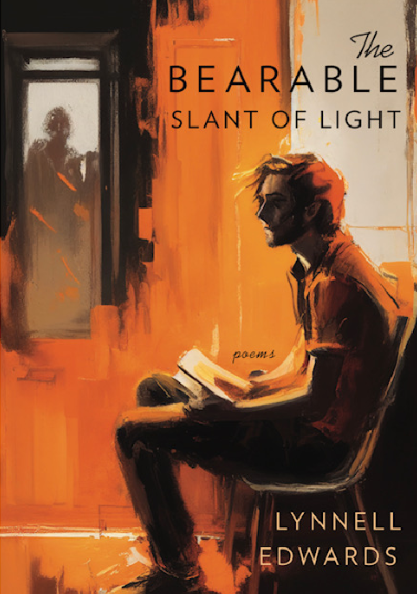

—“Medical History #2,” The Bearable Slant of Light

In the first intake documents from my son’s first hospitalization, the attending psychiatrist wrote: “On examination, the patient presents as a very poor historian.” In other words, he couldn’t tell a coherent and accurate story of what had happened that had led him to bolt from the therapist’s office that July afternoon and subsequently be transported to the hospital for psychiatric evaluation.

Even now, ten years later, it is not clear that he is yet able to tell that story that reflects his truth about what his life is and will be.

I have also tried to answer the question of Did something happen!? with a story that explains my son’s mental health challenges more times, and in more forms, that I can possibly recount. But as someone who teaches in a graduate creative writing program, my accounts never actually feel like anything I recognize as a story. There’s no inciting incident, there’s no protagonist, no identifiable conflict, and certainly no resolution.

There are characters, sure: the wide-eyed young social worker who really wants to help; the weary but wise nurse practitioner who has seen everything; the eager resident who has a new idea about new meds; the harried doctor with 15 minutes to assess the case and then solve it all with a pill or five.

And there are plenty of settings: the suburban office of the first therapist where we sat nervously waiting for the results of the assessment, with no sound but the gurgling of a decorative water feature meant to inspire mindfulness; the waiting area of Emergency Psychiatric Services, shaking with fear for his life after a self-harm event; my bedroom in the middle of the night, when I am startled awake by the phone and questions from a social worker about his mental state; in the parking lot of his apartment explaining to emergency responders that he suddenly started shaking and then became unresponsive; late at night over too many glasses of wine with dear friends who sit on our back deck and listen patiently to the “story” of the latest failed hospitalization.

The only way to tell it, for me, is poetry. My conversation with Dr. K, quoted above, opens the first poem in my new collection, The Bearable Slant of Light, which documents my son’s struggles and diagnosis of bipolar disorder, as well as the contours of our anxious culture. As the poem lays out from the start:

The hospital happened the involuntary happened the injectables happened they had to rip his shirt the doctors the nurses the residents the techs happened the other patients some of them pacing in the hall and loud the first attempt happened the one-on-one happened the eeg happened the ambulance happened none of this is in any kind of order you understand the restraints and psychosis the overdoses and noncompliance the catatonia the mania happened the loneliness the isolation happened so many many different meds the assessments and telehealth happened more ambulances happened the courts happened the ect happened the second attempt happened the social workers happened the intensive outpatients and treatment teams and therapists happened seven years happened he won’t get them back

I wrote this because I had to. Because the story that helps him and helps us, and helps everyone who loves and cares for him make sense of the last 10 years of his young life —the story that would be the foundational story of identity and acceptance — has not cohered. Did something happen? we keep asking ourselves. And if we understood what had happened, then perhaps we could answer the more important question: What’s going to happen next?

As a writer, I am compelled to make it make sense, to build a narrative in which he achieves what he set out to achieve with this life though this was no more clear to him now than it was when he was a 20-year-old just beginning the journey into adulthood. That’s when a psychotic break first hit him. And here, even the narrative implications of the word “journey” suggests that while there might be obstacles, there will be an end — whether for good or for ill.

But storytelling devices never seem to add up to more than the sum of their divergent parts: the illness metaphors of struggle and sturdy survival (he beat the odds! he battled back!) or graceful acceptance; the predictable plot twists and turns of remission and flare-up; the clear successes and failures of any one treatment; the clinicians that don’t fall easily into categories of heroes and villains, each with their own story of motive and intent..

So it’s hard, if not impossible, to impose on my son’s story any kind of literary “sense.” As a writer and a mother both, this has been my challenge.

The language of poetry can tell a different story

To be sure, there have been possible candidates for narrative subjects — ways to spin a tale about “what happened.”

There is, for instance, the story of medication. It began with an antidepressant and was told to him like this: You won’t really notice anything for a month or so, and then you’ll realize you just feel better. Instead, twenty minutes after taking the pill, a different story emerged of a laughing, crying, twitching, pacing, sleepless 72-hour freak-out. While this manic response to Luvox should have been a tip-off, he sort of stabilized at a lower dose and persisted for a while until finally abandoning it. Did it work? Was he better? Worse? Changed? Was this progress or decline? Surely, something worth telling had happened.

What happened next, of course: hospitalizations and more medications. An antidepressant was the first drug, but it was hardly the last; a protocol of polypharmacy including meds to alleviate the side effects of other meds meant it was never clear which ones were providing what kind of relief, if any. I needed to shape the story of them (so many, many meds) as something entirely different, something that was more than just information about neurological receptors and physical side effects. Mark Freeman, in his discussion of the psychological humanities, points out how it is “… important to find a language to be able to speak to experiences that are not readily articulable, explainable, and so on. And that also means moving into a different register of language…”

Here, the language of poetry can tell a different story of medications. For instance:

Celexa

Hell no he wouldn’t take

it again. He knew

it wasn’t right, felt it buzzing

in his veins like a trapped

fly. Wouldn’t take a pill

that sounded like the name

of a goddamn luxury sedan,

smooth over winding

mountain roads, silent

into an inferno of fall colors,

flaming in a distant state.

And:

Depakote

Might as well be

called dead-a-kote –

a dumb blunt of

a drug dosed

by the 500 mg

slug. Thuggish,

old school knock-out.

Then there are the stories of the assessments, the inventories, and exams and bubble tests that are meant to measure. But my son was essentially unmeasurable. Freeman, in his interview again, refers to the “arsenal of instruments” psychology offers in its attempt to diagnose, concluding: “One of the faults of academic psychology is that through its vast arsenal of methods and techniques, scales, and measures, it has beclouded our own encounter with elements of human reality that precede all of that arsenal of instruments.”

Then there are the stories of the assessments, the inventories, and exams and bubble tests that are meant to measure. But my son was essentially unmeasurable. Freeman, in his interview again, refers to the “arsenal of instruments” psychology offers in its attempt to diagnose, concluding: “One of the faults of academic psychology is that through its vast arsenal of methods and techniques, scales, and measures, it has beclouded our own encounter with elements of human reality that precede all of that arsenal of instruments.”

Another way to say it, as I wrote in “The Results of the Assessments I,” a poem about the merry-go-round of psychological inventories and instruments: “What we observe is what we want to see.”

But I also looked to literature and history for representations and stories of mental suffering. In the most true of these fictional stories, there are rarely good ends: Quentin Compson’s psychosis spiraling into suicide in The Sound and the Fury; Holden Caufield telling the story of his breakdown from a residential psychiatric facility where he has been sent to recover; King Lear’s youngest daughter Cordelia remaining silent until her death. Though armchair diagnoses of fictional characters (the most famous being Freud’s analyses of Hamlet) can distract us from the beauty of the tale at hand, these characters were a way to refract the light of our experience through a different lens, and perhaps see it more authentically. My son is not Holden or Quentin or Cordelia, but there is a flash in what these writers have captured that invites more expansive thinking, ineffable language about what happened, and the emotional burdens of loss, anger, and despair these experiences carry.

Stories of who we are, how we got here, and what shaped us are perhaps now more than ever at the forefront of our cultural landscape. The rage for personal DNA profiles that will tell us our ethnicity and migration stories, and the celebrity gotcha drama of Finding Your Roots, all suggest how fundamental our “stories” are to understanding who we are.

But for ten years, my son and all those who love and care for him have had no coherent story to tell. I have tried to tell a kind of story in my poetry because it is all I can do to save myself. If it is chaotic, unresolved, but with flashes of beauty — much like everyday life — then I will have succeeded. The false and partial stories of drugs and the “arsenal of instruments,” along with the hundreds of pages of intake and discharge papers, do not tell us — or him — what we need to know.

He must fashion his own story with its own expansive narrative mosaic of chaos and beauty. He must become his own historian.

The force of pain and emotion demands expression in form, and if you put it in the form of poetry, the force of this pain/emotion is conveyed mimetically to the brain, because notice this one crucial thing. When you are afraid, the force of the fear expresses itself into the form of imagination, which then displays and conveys the fear to the brain and via the brain, the whole body, by way of an animation. The form of the imaginative animation clearly comes from memory, and the force behind the animation is clearly from the feeling of fear. Same too if you are lustful, the form of imagination conveys the force of the feeling, and the animation displays the desire to the brain. Now, PTSD – traumatic complexes – and psychosis are no different, and neither are the non-ordinary experiences associated with the new rage which is psychadelic therapy. These non-ordinary animations draw for their form on our memory, but the force or energy behind it is feeling, or emotion, or traumatised life energies, or spirit: these are so many words for a phenomena that YOU ARE and therefore don’t need to put into words. You can look within. The reason why psychadelic therapy works is because they convey the content of pain to the brain, and what we call psychosis and PTSD is this same natural healing mechanism being attempted but because we don’t understand the phenomena and have only socially conditioned opinions, theories, assumptions and other non-facts about them, we run away from or frustrate these attempts at healing and therefore never healed. I healed my ‘psychosis’ and ‘PTSD’, and indeed trauma and depression more generally, because society abandoned me and therefore left me to my own nature. It is nature that heals and society that destroys, so in abandoning me, it set me free.

Report comment

Society is the bad breast. The good breast is green. The good breast is nature.

Report comment

I’m sorry your son got caught up in psychiatry’s iatrogenic bipolar epidemic. Sadly, I did too – same etiology, too … misdiagnosis of the adverse and withdrawal symptoms of an antidepressant as “bipolar” … followed up with a whole bunch of anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

Then, if you’re lucky enough to get (even slowly) weaned off the psych drugs, you can end up dealing with a drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity mania and or manic/psychosis – which, of course, gets misdiagnosed as “a return of your illness.”

There are lots of us here who have dealt with this type of “complex iatrogenesis.” And I’m guessing your son’s healing journey will look a lot the same.

“He must fashion his own story with its own expansive narrative mosaic of chaos and beauty. He must become his own historian.”

“There’s no inciting incident, there’s no protagonist, no identifiable conflict, and certainly no resolution.”

I agree, your son must be the “protagonist” in his own healing journey story. I did, and do still need to be in my life’s story, too. Unless, I find an actual writer who’d like to write my story, since I’m not a writer, and am also a woman who was taught by my society to be modest, so writing one’s self as one of the “heroes,” in their own healing journey, is difficult for me.

In my story the “inciting incident” was distress caused by 9.11.2001. The “identifiable conflict” was with a did-not-know-me pastor, who unjustly denied my innocent child a baptism on the morning of 9.11.2001.

And the “resolution” / “elixir,” aside from being weaned off the drugs, was to also finally be handed over medical evidence that the pastor’s best friend was a pedophile, and my PCP’s husband was the “attending physician” at the “bad fix” on a broken bone – everyone’s motives were then made clear.

Mine is a story that begins with “Oh what a tangled web we weave/When first we practice to deceive,” followed by lots of research on the World Wide Web, and it ends with “the truth shall make you free.”

Please do know your son can heal, but it will not likely be an easy journey. And God bless your entire family, for helping your son during his healing journey. Support from friends and family was invaluable for me, when I was going through the living hell of psychiatry’s iatrogenic “bipolar” epidemic … and my subsequent healing journey. I’ll say a prayer for your son.

Report comment

But you don’t understand – the poetic utterance and the cheetah are God. They are the force of the Mother through the form of the Father, and it explodes into infinite colour. You are the force of the Mother and the form of the Father. You are feeling and mind. Mind is sky is God. Body is Mother is God. They are the form and force which though different, can never be apart, and everything is that. It’s the bow and arrow. It’s the vessel and the space within. You are that space and that vessel. You are God and Mother Earth. This is a fact. The other stuff, energy, is the movement their estrangement creates. This is the secret of male and female, good and evil, Mother and Father. They estrange themselves from themselves in order to create the passion of existence, and it’s so obvious to any sea slug, river or galaxy or planet or snail. Even your own consciousness knows, but it’s patient and allows the brain to learn at it’s own glacially slow pace.

Report comment