A new article by psychosis researcher Lex Wunderink suggests that antipsychotic drugs can be safely and effectively tapered without increasing the risk of relapse. The keys, according to Wunderink, appear to be tapering more slowly than previously thought and involving the patient and family in personalized decision-making.

“Many patients with psychosis want to discontinue their antipsychotic drugs due to serious side effects hampering their daily functioning in the long term. The main drawback of discontinuation is relapse. Modern tapering strategies seem to reduce relapse risk to an acceptable level,” Wunderink writes.

He adds that although these findings still need replication, several studies are already being conducted that could provide confirmation and further details about the best tapering processes.

According to Wunderink, antipsychotic drugs can be effective in the immediate treatment of psychosis—reducing the hallucinations and delusions that are hallmarks of the syndrome. However, he notes that the drugs come with harmful effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction, tardive dyskinesia, metabolic syndrome) and even worsen the so-called “negative symptoms” of apathy, anhedonia, and cognitive impairment. Due to the strong negative effects on quality of life, many patients want to reduce the dose or eliminate the drug altogether.

According to Wunderink, studies have shown that it is actually possible to do so without any increase in relapse risk. A 2023 study demonstrated that using a personalized, slow taper, 74.5% of patients were able to reduce their dose and end up with better outcomes than those who kept taking the drugs. Only 11.8% experienced relapse—a rate comparable to those who continued taking the full dose of antipsychotic drugs.

He writes, “After remission of the positive symptoms, antidopaminergic drugs may do more harm than good, unless they are necessary to prevent dopaminergic derangement in vulnerable patients: We must find the lowest antipsychotic dose that prevents positive symptoms to reemerge in every individual case.”

Wunderink also cites the results of his seven-year follow-up of people reducing their antipsychotic prescription. While the initial two-year trial showed a higher risk of relapse for those who began tapering antipsychotics, after seven years, those in the dose-reduction group were more than twice as likely to recover than those who were maintained on the drugs (40.4% versus 17.6%).

Similarly, a recent meta-analysis found that people with schizophrenia who stopped taking antipsychotic drugs had better long-term outcomes in terms of social functioning, employment, and quality of life. Bolstering Wunderink’s point, that analysis found that studies involving individualized tapering strategies showed the best results.

Wunderink notes that one of the major issues with antipsychotics is dopamine hypersensitization: since the drugs block D2 dopamine receptors, the brain compensates by upregulation. When the drugs are removed, the brain is hypersensitive to dopamine, making the patient more likely to relapse. For this reason, Wunderink writes, a slow taper is needed in order to allow the brain time to adjust to the different levels of dopamine.

“This might explain why multiple-episode and chronic patients generally need higher doses of antipsychotics than first-episode patients, why the incidence of tardive dyskinesia is linearly dependent on the duration of dopamine blockade, and why so-called rebound psychoses occur after abrupt discontinuation of dopamine blocking drugs,” he writes.

As far back as 1967, researchers had identified that outcomes for patients taking antipsychotics were no better than they had been before the introduction of these drugs; outcomes were even, in some ways, worse. In 1976, researchers raised the question: “Is the cure worse than the disease?” This result continued to be found, with researchers in 1977 and over the next few years suggesting that the drugs themselves might be responsible for altering the brain in harmful ways, worsening outcomes for those who used them.

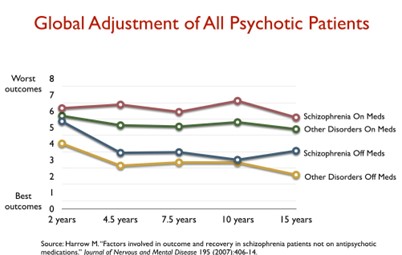

Indeed, an NIMH-funded trial by Martin Harrow and Thomas Jobe found that after 15 years, those who stopped taking antipsychotic drugs were eight times more likely to recover.

They compared outcomes for people with other disorders—not just schizophrenia—as a way of accounting for confounding by indication. Those with schizophrenia (the most serious diagnosis) who stopped taking antipsychotics had better outcomes than those with less serious diagnoses who did take antipsychotics. Those with schizophrenia who continued with drug treatment fared the worst.

This continues to be the main finding of longer-term outcomes to the present day. In a 2023 study of five-year outcomes after first-episode psychosis, researchers found that those who did not receive antipsychotics within the first month were twice as likely to be in recovery. A previous study by the same authors looked at cumulative exposure to antipsychotics for all patients with first-episode psychosis over a 19-year period; that study also found that those who took the most drugs for the longest period had worse outcomes, including higher mortality rates. In both of these studies, the researchers carefully accounted for confounding by indication and other possible factors.

In a 2013 systematic review, researchers found that recovery rates for those with psychosis have declined over time, with a particularly steep decline in the modern era of antipsychotic drug treatment. From a high of 18% in 1941-1955, the recovery rate has fallen to 6% since the late 1990s.

Ultimately, according to Wunderink, due to the powerful negative effects of the drugs, patients will continue to want to reduce or discontinue antipsychotics. Thus, doctors must help patients reduce their dose, lest the patients discontinue abruptly and relapse due to dopamine hypersensitization. The best evidence that exists indicates that a personalized, slow tapering process—with the ability to stop once the patient begins having difficulties—is the best option.

This also has the advantage, according to Wunderink, of enhancing the relationship and trust between the patient and provider, thus enabling better treatment.

Wunderink writes, “We still do not understand the most important mechanisms causing psychosis and relapse, nor are we able to predict who is dependent on antipsychotic drugs after remission of psychosis and who is not. To accept this is important but may be even more important is to work together with your patients and try to find the best individualized treatment for every single person having to deal with psychosis.”

****

Wunderink, L. (2024). Changing vistas of psychosis and antipsychotic drug dosing toward personalized management of antipsychotics in clinical practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. Published online April 22, 2024. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/prj0000614 (Link)

As someone taking a lower dose of Zyprexa for over three years, I can say I’ve been doing much better than when I was on three or four drugs at a time in higher doses. Of course, other things, like a community that enriches my life is super important. I was misdiagnosed with Bipolar at thirteen. I’m autistic.

I have tried three times to taper too fast my antipsychotics, all ending up with me experiencing super sensitivity psychosis, in the hospital. Horrible. No way to advocate for myself.

Thankfully, I found a psychiatrist in 2020 who listened to me and brought my dose of Zyprexa down to 5 mg. I had cut from 30 mg, in the hospital, to 20, to 15, then to 10. My doctor then prescribed the 10 for me and then prescribed the 7.5, then the 5 mg. Last October I cut my 5 mg pill in half, eight days later, two nights with zero sleep, ended up in the hospital. Horrible. But my doctor didn’t let them increase or change meds. Went back home, titrated up to 7.5 but then back to 5mg.

I’m doing well. Very important to slow taper. I’m looking into the Dutch “Rainbow Pharmacy” to do tapering strips. Was thinking of taking one year to slow taper to 2.5 mg, and then to take a break. Anyone on here still on meds but at a lower dose?

Report comment

I’ve been off all psych drugs since 2009. And I will say, Meg, I do think you are going about weaning off the psych drugs in the correct way. I’m glad you’re doing well.

But I will forewarn you, my former psychiatrist spent 3 years weaning me off the psych drugs, once he stopped getting all his misinformation about me, from a pathological lying, child abuse covering up psychologist, according to my child’s and my medical records. But even a very slow taper can result in a “drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis” … so just be forewarned.

God bless, and know it is possible to get off the antipsychotics, Meg. I did it long ago, with no help, and so can you, with your knowledge of the truth. And thank you Peter and Dr. Wunderink for your truth seeking research and reporting.

Hopefully, the tapering strips can prevent a “drug withdrawal induced super sensitivity manic psychosis.” They didn’t exist in 2009.

Report comment

Gradual and papering of antipsychotics is practically possible using tapering strips: https://www.madinamerica.com/2024/04/tapering-strips-a-practical-tool-for-personalised-and-safe-tapering-of-withdrawal-causing-prescription-drugs/

Report comment

A drop in saturated blood oxygen is a bothersome result of psych drug therapy. It happens over time despite exercise. It causes dizziness on standing when spO2 is at 94 or 93 %, so a drop of 2% below normal parameters.

At 88 % you are in Big Trouble and do not hesitate to call an ambulance.

The risk is hypoxia to organs.

I am writing to you to confirm that learning to withdraw while you are able to is better for your body/brain function.

If you experience dizziness and have been told it is an anxiety symptom, ask to have your spO2 analyzed or measured. Normal range 100%- 95 %. I find exercise a great help, also hydration, and having a personal oxymeter. (Or oximeter)

Report comment

Cellular level suffocation from both buildup of blood co2 and lack of o2 to cause dizziness 10x to 20x per day.

Enough is enough really.

All for withdrawal from these psych drugs at this stage.

SpO2 hitting 93%

It is not happening to me, God willing won’t, but I have the trauma of witnessing it vicariously for one thing.

So strange.

Report comment

This comports with my own experience. Trying to figure out the minimal effective dose for each individual is a harm reduction approach. A “relapse” for one person may not confer the same risks as it does for another. Also, the risk of a resurgence of psychosis may change as the dose is reduced so a person might chose a goal of getting to a low dose where there are fewer unpleasant effects rather than stopping completely. Open discussions about the known and unknown risks is valuable. I have also found that shifting to a drug-centered (vs disease-centered) discussion of drug effects (as Joanna Moncrieff has described) is helpful.

Report comment

Thank you for the article but when are the prescriptions going to stop? People given contaminated blood products have been recognised and hopefully will be compensated. When are these prescribed drugs going to be recognised as extremely harmful to many people over many years? This is not accidental – it is intentional and produces harm to many and profits to the producers and distributors. We need action to stop this harmful practice!

Report comment