In 1936, at age nineteen, a German woman named Dorothea Buck followed the trail of a star along the mudflats of her North Sea home, Wangerooge Island. Rapt, she spent the night under a dune and was brought home in the morning by local workers. Buck had been experiencing a series of visions. One of these was that her country’s chancellor, Adolf Hitler, would start a war that would become “monstrous.” No one believed her, and as Buck asked the adults in her life to help her stop this monstrous war, the vision became a psychiatric “symptom.” Hospitalized at a Christian institution called Bethel, diagnosed schizophrenic, Buck was sterilized under the Nazi law for prevention of hereditary diseases.

Buck, who lived to the age of 102, fought throughout her life for psychiatric reform. She created her own form of mind care, which she called “trialogue.” Buck refused to dismiss the meaning of her psychotic visions or reduce any neurodivergent state to “biological brain disease.” In trialogue, psychosis experiencers, family, and clinicians worked as equals, with respect for the value and knowledge of both experiencer and experience. Buck also demanded recognition of the Nazi murders of the disabled and the mentally ill. Many of these victims were psychiatric patients gassed between 1939 and 1941 in chambers built into German asylums.

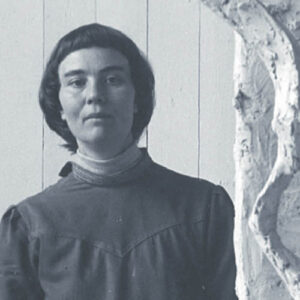

I first encountered Dorothea Buck in 2019. Buck died that fall, at the age of one hundred and two, as I was having a psychotic episode. I learned of Buck’s life and her book through an obituary in The New York Times. I found her memoir, On the Trail of the Morning Star: Psychosis as Self-Discovery, and had it translated by the wonderful Eva Lipton. Buck wrote her story at the urging of journalist Hans Krieger, and the book appeared in German under the pseudonym “Sophie Zerchin”—an anagram for the German schizophrenie—in 1990. I encountered a thinker who captured not only the buffeting of neurodivergent experience, but its corollary: the mind engaged in a process of world-making, a making that functions through its own channels. Buck taught me a new respect for the wildly creative work of consciousness.

On the Trail of the Morning Star, from which these two excerpts are taken, appeared in English in May of 2024. It’s available at punctum books, as a physical book or a free download. Buck would have wanted that. Both excerpts describe places where, as Buck acerbically put it, “I had sworn to myself that I’d rather stay mentally ill than ever take part in having the ‘mental health’ being demonstrated here.”

****

Excerpts from On the Trail of the Morning Star: Psychosis as Self-Discovery

The first excerpt describes Buck’s experiences in Bethel during her 1936 hospitalization, including her sterilization. Buck was shocked to find inner experiences she found deeply meaningful dismissed as meaningless physical disease. Ignored, tormented by treatments like wet wraps, witness to the brutalization of other patients, Buck later called the Protestant institution of Bethel a “hell amidst Bible quotes.”

A human being can hardly be degraded more. The doctors and nurses who know nothing and want to know nothing about the history and the contextual meaning of the psychosis and think everything is just a meaningless side effect of a physical disease, probably never think about how they degrade and devalue us. As long as they don’t talk to us, they cannot know anything about us.

Was I supposed to recant what I had experienced? Is that what they wanted? Did the old authoritarian demand of the church to recognize only what fit their ideas of God’s path for humans, and keep people from questioning their role as mediators, present itself in a new form of resistance, one that was more contemporary than medieval methods? I swore that I would never exchange what I had experienced as God’s guidance for the “true Christianity” that was being modeled here. Following each narcotic injection and each little glass of paraldehyde [a powerful sedative] I was given, I insisted to Nurse Y. that none of this would ever change my mind, and I repeated this until I passed out.

On the green wall across from me painted in large letters was Jesus’s quote: “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest [with the sense of ‘refreshment’ in German].” Refresh—with long baths and wet wraps, with cold water showers on the head, with narcotic injections and paraldehyde. That was absurd and incomprehensible. I had to think of God calling the devil “the father of lies.” And then something happened that made an indelible impression on me. Frau Pastor H. was cleaning the hall dressed in the blue-striped ward uniform and talking to herself. Maybe the tone was aggressive and maybe she looked at Nurse Y. Regardless, [nurse Y] suddenly grabbed the Frau Pastor’s long hair, pulled her down to the ground, and dragged her across the floor by her hair. She passed the Bible quote going into the bathroom. Like a strong field horse in front of the plow she looked at us—an unforgettable image of brutal violence and unprotected impotence.

Decades have passed since then and still that image is embedded in my mind’s eye as if it happened yesterday. And that is probably how all of us affected ones feel who have had the most harrowing experiences in our asylums—possibly in Christian asylums with Bible quotes on the walls. If that is supposed to be spiritual health—it could not convince us. We learned to fear this type of “spiritual health.”

Later a young aristocratic woman joined, Fräulein von W. She had been operated on recently. She kept getting up from bed. What were those peculiar scars that she and little R and little P had above their vaginas? I asked Nurse Y. “Appendix scars,” she explained. Earlier on I’d learned that the appendix was located on the side. Had we been lied to about that as well?

In the institution we were robbed of our dignity; we were reduced to being objects to be kept and observed. We were objects to whom it was not worth talking, and who were not worthy of occupation or else considered incapable of being occupied. And to be unable to talk to anyone about it was the same as total inner isolation. As much as Bethel tried to fight my experiences as the expression of “mental illness”—for me they remained something very essential.

In the meantime, I knew we were being kept here because we were “mentally ill.” And I had sworn to myself that I’d rather stay mentally ill than ever take part in having the “mental health” being demonstrated here; it seemed to me not worth aspiring to.

One evening—it was September 17—the friendly ward nurse M. shaved my pubic hair after my bath. Why? I wanted to know. “For a necessary little procedure.” It was obvious that she didn’t want to provide a more detailed explanation and I didn’t ask any further. I had no idea about a sterilization. That is why I hadn’t had any doubts when Nurse Y. referred to my co-patient’s scars as “appendix scars”; many, after all, had their appendices operated on. And I never would have thought it possible such a serious procedure could be done without first talking about it to the concerned party.

Early in the morning, Nurse M. took me to the Gilead hospital. I felt no fear at all as I stood alone in the antechamber of the operating room in my white cotton socks and short shirt. For the first time in more than five months I was able to open a window all the way, and I felt such happiness about this wide open window on a bright morning with the sun rising. I still had no idea what they planned to do with me.

Nurse M. entered and was visibly startled to see me standing at an open window. The thought of jumping out of it had never crossed my mind. She quickly closed the window, and I got on the gurney that was rolled into the antechamber. The anesthesiology nurse—I still see her face—injected my arm and I sank into the unconsciousness I was already so familiar with, though it was faster. than I was used to. This injection worked much faster than the ones that Nurse Y. jabbed into my thigh, once with such force that the discoloration of the skin can still be seen today.

I woke up out of anesthesia in the little four-bedroom area in the ward for the depressed. Now as well, nobody informed me what kind of procedure had been performed.

Another patient, a deaconess who had been living here a long time following an auto accident, explained to me that the operation was a sterilization. She had brought flower garlands she made herself to my sickbed. Without her I would probably not have found out anything in this house.

I was in despair. I had my hair cut, because I at least wanted to watch my hair grow if everything else in my development was to stop.

****

This second excerpt describes Buck’s fifth hospitalization in 1959. The relatively new emphasis on psychoactive drugs rendered Buck semi-conscious and she spat out her pills. Though thirty years had passed since Buck’s first hospitalization and National Socialism was over, little had fundamentally changed—care remained negligent, dehumanizing, aimed at suppressing patients’ inner experiences rather than exploring them. Buck and her fellow patients began to speak to each other about their inner lives, and their conversations and mutual support became the roots of Buck’s later psychosis seminars.

I lay in the large admission hall with a number of rows of beds. The female patients lay next to each other one bed after the other, only separated by a nightstand. All of them were sedated with injections. I hadn’t experienced that yet: that we should be incapacitated with psychotropic drugs right after being admitted and then kept sedated. In a brief time, we were also so physically weakened that I stumbled to the bathroom on unstable legs. I had to hold onto the edge of the bed in order not to fall. My hand trembled so much that I could hardly hold the cup and spilled my coffee.

“Don’t carry on so!” the young nurse barked at a female patient who buckled on her way to the bathroom. That was the most eerie part of what I experienced in the institution: a large hall full of intentionally weakened, half- or fully sedated patients. The doctors barely knew what was going on, what they were experiencing, but they had the authority to take our last bit of freedom in a locked house: the freedom of our thoughts, our consciousness, and our bodies.

Even if we were put into duration baths in Bethel in 1936, or got sedative injections, once we woke, we were fully present again and not weakened physically. We didn’t have to swallow our fear and our resistance but could express them anew. Is this forced silence really progress from the “restless wards,” with their justified resistance against psychiatric methods, which fight and devalue the patient and their experiences?

I protested against the forced injections, I tried to explain that my previous break had receded on its own without medication and had actually led to a break-free period of thirteen years. The medication-induced interruption of the psychosis had led to new outbreaks after just five and three years. None of it helped. “Just leave it to us,” one of the doctors in the admission ward said. “We can already see what is going on with you.” The experience of the patient and the meaning it has for them didn’t interest our psychiatrists. They were only interested in the symptoms and behavior that deviated from the NORM. The power of these psychiatrists to force their limited viewpoint on us with medication is frightening for us.

Luckily, I got a rash after three days, so the injections had to be stopped. Instead, the nurse now stuffed pills in my mouth. I had to suffer it, but she didn’t force me to swallow them, as is done nowadays. I kept them under my tongue and waited for an opportunity to flush them down the toilet when nobody was looking. None of the doctors noticed that from that time, until about eight weeks later when I was discharged, I had not been medicated. Prior to being discharged I told the ward doctor that I had never swallowed pills. “We have to treat with medication,” he noted, “insurance demands it of us.”

For the first time, however, we tried to help ourselves on this ward. The summer of 1959 was very hot, so we were allowed to stay in the little ward garden most of the time. A group of about eight female patients sat on recliners that were shoved together and talked about what had struck us most during our psychosis experiences. This way we could give one another confirmation of the meaning of our experience and separate ourselves from the devaluing psychiatric evaluation that undermined our confidence. These hot summer days, above us the crowns of the pines in whose shadows we discussed our psychosis and dreams in a relaxed way, and thought about them, belong to my good memories of my time in institutions. It is the fellow patients through whom institutional time becomes rewarding, because they have known what psychosis is and know more about it than specialists. The specialists neither have the experiences themselves, nor are willing to learn about them by talking to their patients.

For a female patient in her first break who only heard individual sentences, it was still impossible to see a meaning in them; she couldn’t understand the context and connection. Those of us who had experienced a number of breaks and thus had more comprehensive psychosis experiences found it easier to recognize the meaning.

This patient told me about experiences of everything unifying. She much later read about similar events in the biography of an East Indian. She was a woman with a simple background, and she could hardly have known about the book. Aside from such happy experiences, she had a compulsion to add up people’s value by the numerical value of the letters of their names. Where nothing could exist without meaning, even names had to have a secret meaning. In the book Mysticism and Magic of Numbers by F.C. Endres I later read, as I found out about psychoanalysis, that this same transformation of letters into number values and vice-versa had occurred two hundred years earlier among Kabbalistic scholars. That it is much older may be indicated by Roman letters that represent number values. If this patient could have seen such parallels, then she could have understood her compulsive behavior better: a breaking open of “archaic idea possibilities,” as happens in schizophrenia according to C.G. Jung. Perhaps they would then have lost their compulsiveness for her. What one understands affords one more freedom.

Our psychoses had receded. My fellow patients had been suppressed with psychotropic drugs, in my case, the break had receded without medication. We had grown our thick skin back, the close community began to disintegrate. I felt again the slow abatement of the strong impulses of the acute break into just a quiet instinct, as with the previous break, which had also not been interrupted with medication.

We were close to being discharged.

The 21th century’s psychiatry isn’t better significantly.

Report comment

Was thinking this all throughout reading the article.

Ableism, medical neglect and medical gaslighting doesn’t even have much of a platform

Report comment

“Buck had been experiencing a series of visions. One of these was that her country’s chancellor, Adolf Hitler, would start a war that would become “monstrous.” No one believed her, and as Buck asked the adults in her life to help her stop this monstrous war, the vision became a psychiatric “symptom.” Hospitalized at a Christian institution called Bethel, diagnosed schizophrenic, Buck was sterilized under the Nazi law for prevention of hereditary diseases.”

I don’t really know anyone with “schizophrenia” who doesn’t have an outlook on life they aren’t supposed to entertain, and is in many ways more sane than the whole kit and kabootle lacking the color to see what they [the “insane” one] are talking about.

What’s quite remarkable, is that after the whole war, she wasn’t supposed to have any inkling of was over, she ended in an asylum again!

Report comment

One thing that hasn’t changed in psychiatry and in dominant social attitudes since the 20th century with regards what we call ‘mental illness’ is that all the thinking and psychiatric concepts are defined first by outward presentations of the conditions rather then an investigaion of the inner states, and secondly, that they are socially and psychologically normative – they define ‘mental health’ as normal egoistic functioning and normal socially conditioned behaviour, and they define pathological as non-ordinary mental states and behaviour, which means we don’t actually see the condition or attempt to understand it at all: rather, we see all the devience from the norm and judge and conceptualize the condition accordingly through an analysis of outward presentation, without any serious concern to uncover the actual inner psychological states, or to put it another way, to explore the phenomenology of the experience. Few exceptions to this have been Laing’s existential psychology, and Jung’s psychological insights which developed through deep self-enquiry and non-ordinary experiences that today we might regard as ‘psychotic’ in character. The key problem with all of this is that the ordinary social psychology of selfish individualistic egoism, and the normal socially conditioned behaviour of becoming a confused and unhappy, striving person whose behaviour is contributing to the destruction of the Earth and all our children’s futures, is not looking quite the model of sanity it did in the Early twentieth century, and just as the whole of civilization seems to be unravelling, in psychiatry and in the contemporary society we are seeing the destructive consequences of the ordinary social psychology with the proliferation of total delusional beliefs and conspiracy theories, with the proliferation of political and social divisions, with the massive inrease in mental illness, drug and alcohol addiction, homelessness and gun crime in the US, knife crime in the UK and so forth, the norm is destroying us all. So let’s destroy the norm. We have to destroy the system that’s destroying the Earth, but that system is also in our heads, hence the modern interest in psychedelic therapy which disables the default mode network in our brain and helps us to wriggle free of our socially conditioned factory consciousness. I had psychosis for years but an intensive period of psychedelic use helped me to go beyond it and gain invaluable learning along the way. Perhaps the greatest danger for us today is thinking and behaving in the normal, socially conditioned, destructive way.

Report comment

It is good to be reminded that human nature doesn’t change albeit the details have changed. The Power Imbalance remains and harm continues. Advocates for humane care walk a fine line. If we refer to the 1930s then we can be misconstrued as out-of-date and misinformed. So we do the best we can to speak from our own observations and experiences. The advances in research, which regretfully have been made at the expense of patients, validate all the axes of the needed, higher standard of care. These two elements: our witness to harm and the truth about the foundations of health inform our advocacy. A third element could be added: that is to honor the ways different cultures have nurtured their young in context of their own survival challenges; the juxtaposition with today’s psychiatric state is compelling.

Report comment

During my daughters second major psychotic break recently, while I was with her in the car desperately trying to find a hospital to bring her to where she could be safe, or while sitting with her waiting for the intake process, I had a chance to talk to her and listen to her in the full bloom of her psychosis. The things that she said were sometimes alarming and often profoundly beautiful and painful. I wanted more than anything for her to be safe and to be cared tenderly. I wanted her to be respected and to be nurtured through the pain she was experiencing. I knew though that the best that I would probably get for my daughter would be drug induced stupor but I had little choice. Her life was at risk and I knew it. As she cycled through states of paranoia and delusion and incredibly sweet childlike innocence, or unbearable philosophical introspection, I had the strong feeling that she was very close to truth, too close to avoid being burned by it, and I tried my best to honor what she was experiencing. In the heavily institutionalized year-long process of recovery that would follow I believe I was the only person who had this perspective.

Gregory Bateson observed in “From Versailles to Cybernetics” that “If your universe is crazy then you are, that is if you try to be sane.” It is an interesting essay and these are words I often return to as a historian and social theorist.

I understand some of the trauma that my daughter has experienced in her family life and in the world and my heart is broken because of it. I was so fearful for her life in the moment of her psychosis that I could only desperately try to find safety for her. I understood the very real danger And had experienced it before in her first episode. She is a wonderful artist but there was nothing artistic about the tremendous pain and confusion she was experiencing. I experienced the greatest heartbreak that any father can experience, watching the grotesquely insensitive staff and doctors that I entrusted her with mismanage my daughter’s mental and physical health. My daughter was treated horribly and pumped full of drugs despite my desperate pleas to the contrary. The system so deeply broken that in comparison to it my daughters psychosis almost seemed more true and genuine. However this provided very little comfort to my deeply broken heart.

Thank you for sharing the story of a woman who was strong and courageous enough to affirm her own psychosis and active meaning making in this world. What a utopian vision to think of her reclining together with her friends in the garden of the asylum talking freely and reflecting together on what they had experienced inside themselves. I know that it is a far cry from any of the group sessions my daughter experienced in the long course of her heavily medicated care.

I believe that there is a basis for sanity but it does not exist in the dominant mores of culture and science. It is a singular oddity that the word apocalypse in Greek means revelation. I am not sure what to make of that historically speaking and frankly I am not interested because we are today faced with a number of serious challenges like this for which we desperately need some philosophical, theoretical and very personal insight. If ever there was a time for revelatory insight it is today and from the story that you have told it seems clear to me that it will not come from the doctors and the scholars and experts but from within the courage and instinctive mutual kindness of the victims.

I only wish that there were more of those meetings on recliners in gardens amidst all of this chaos and insensitivity. And in that spirit of open sharing I thank you again for your story.

Report comment

After over 20 years of psychiatric “care” and gaps where care was not available, safe to say humanity still needs a lot of help with mental health. We’re in a shambles. While ethics are arguably better than the ’30’s, there’s plenty of room for improvement in patient care. And taking care of the providers actually trying to help their charges. Hospitalizations, 30+drugs/combos, bad docs, bad diagnoses, bad therapists, ECT (should be outlawed), TMS, and lots of different behavioral therapies. That’s just me. Can’t count on my fingers anymore how many have been lost to suicide along the way. Mental illness makes life hell. Every day is a battle. What works with all 3 proper diagnoses better than all of the chemicals and most of the treatments? Customize it, but grounding is a great resource. Finding what works for you is key. It could be a literal life saver. Of course keep up with your treatment plan and get the help you need, just put it in your survival kit. Practice it regularly so it becomes muscle memory. When you feel an episode of whatever coming on, start grounding. Your body kinda takes over until your brain and heart stop suffering so intensely. Then you soldier on. Breathe in, breathe out, one foot in front of the other til you come out the other side. Good luck out there, I’m praying for you.

Report comment

I would like Susanne’s email

address. I experienced a rape

by an older student at Stanford

in 1956. I sought refuge in

psychiatry and was threatened

with a lobotomy for my trouble. I’m still in recovery from “adverse childhood experiences”. Check out my

blog: ramax9.blogspot.com

Report comment