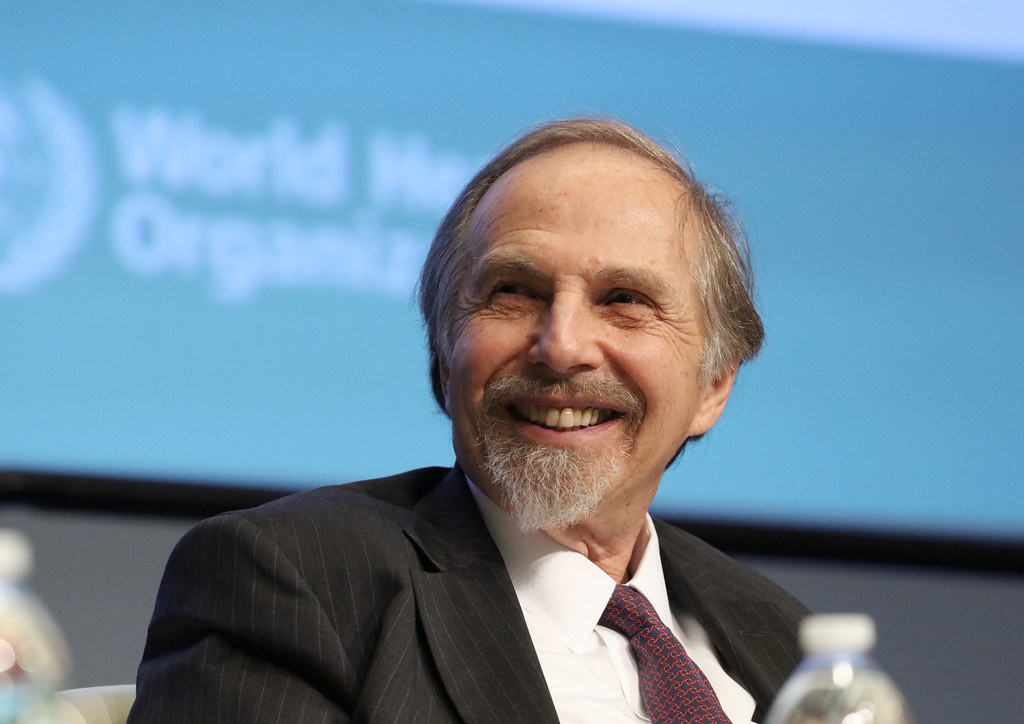

Arthur Kleinman is a towering figure in psychiatry and medical anthropology. He has made substantial contributions to both fields over his illustrious career spanning more than five decades.

As a Professor of Medical Anthropology at Harvard University’s Department of Global Health and Social Medicine and a Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Kleinman has profoundly influenced how medical professionals understand the interplay between culture, illness, and healing. His extensive body of work includes seminal books and numerous articles that have become foundational texts in medical anthropology. These writings explore the crucial role of personal and cultural narratives in shaping medical practices and patient care.

In recent years, Kleinman has increasingly focused on critiquing the prevailing practices within psychiatry, particularly the over-medicalization of mental health issues and the neglect of broader social and personal contexts that significantly impact patient care. His critiques advocate for a more nuanced and compassionate approach to psychiatry, one that recognizes the importance of individual patient stories and the socio-cultural dimensions of mental health.

In this interview, Kleinman explores critical issues facing modern healthcare. He discusses the often-overlooked narrative of patient experiences, critiques the mechanistic approaches that dominate U.S. healthcare, and offers insightful reflections on the global mental health movement.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Ayurdhi Dhar: Could you tell us about your most influential works—what are illness narratives?

Arthur Kleinman: Everyone who falls ill with a serious illness like heart disease, diabetes, or mental health problems develops a story about their experience of illness. Medical anthropologists make a distinction, where ‘illness’ stands for the experience the person has of symptoms, of seeking help, and of responding to treatment from disease, and ‘disease’ is the way that practitioners, not just biomedical practitioners but alternative and complementary practitioners as well, reconstruct the illness experience in a particular set of categories.

Let me give you an example. You’re short of breath all the time, and the doctor says you have asthma. That’s a reconstruction of your experience of wheezing. It’s a very important reconstruction because it usually leads to an effective intervention like medication, but in that reconstruction, something gets stripped away, and that is the human aspect of the illness experience, the way it affects you as a human being. When you’re being treated for asthma, that fear you have of the shortness of breath, that anxiety over the wheezing, that difficulty that you have in doing your work, or in having conjugal relations with a spouse, or in being able to supervise your children—all those things disappear and the disease becomes a very limited pathophysiological focus that allows for a technical intervention— something gets lost in that transformation.

The practitioner doesn’t pay sufficient attention to who you are as a person, to what the illness is doing to you, and the constraints you might find in following the treatments. Think of an Asian or Asian-American individual who has high blood pressure. They use soy sauce for cooking, which is 16% salt. In hypertension, it’s critical that you limit your salt intake. Just being Asian-American and eating a diet that is informed by the wonderful traditions in Korea, China, and Japan means that either the whole family changes its orientation to food or the person with hypertension is going to be, in a sense, left out. Does that get taken into account by doctors? Generally, not.

Every one of us has specific examples where a treatment interferes with certain aspects of our lives. The practitioner needs to take those aspects into account because in order to follow the medical regimen, we have to be able to have a life.

Just think of the consequences of taking certain mental health medications, such as antidepressants, that are associated with weight gain. Serious weight gain can be the difference between feeling good or bad about yourself. If you feel bad about yourself, that’s not going to assist in getting rid of depression. It’s likely to make it more difficult to get rid of. Being aware of the psychosocial context in which the patient lives is critical to care.

In theory, psychotherapists should consider the context. But do they? They don’t sufficiently. In medicine, the tendency is to forget about the person and their context and just treat you as the disease. In the mental health field, the tendency is to focus on you as an individual and forget that you live in a family, in a community, and work with others. Leaving out that social context can be the difference between effective and ineffective treatment.

Dhar: I was thinking about sexual dysfunction as one of the side effects of antidepressants. When you’re already feeling low, and the one thing that allowed you intimacy with your significant other also breaks down, creating further isolation, that cannot help. You write that the way we train physicians, including psychiatrists, makes them blind to patients’ and their families’ illness narratives. There is something in the culture of medicine. What is the cost to the patient and to the physician?

Kleinman: We have at least eight studies that show that if you compare first-year and fourth-year medical students’ interviewing skills, in paying attention to the person and the social context, first-year medical students are actually better. That’s deeply disturbing.

The system of healthcare today in America is toxic to good care. It produces burnout. Physicians are expected to give care. But the structures we have—the system of caregiving, the enormous importance of finance in caregiving, the idea that patients are profit centers—undermine care. It ties the hands of the practitioner behind her back, even if she wants to get the illness narrative.

“That is a system of care built around the idea of efficiency, not of care. All these statements that are made in the mental health field about quality of care are frankly bullshit. We do not measure quality. We measure institutional efficiency.”

To measure care, you would have to measure the quality of relationships, communication, clinical judgment, treatment decision-making, and patient’s feelings about following medical advice or not. All of that would be in quality of care. We measure satisfaction—are you satisfied or not? But these are meaningless questions.

Psychiatrists have been turned into prescribers of medication. That is the role that the healthcare system forces them into. Healthcare insurers would much rather pay social workers to do psychotherapy than they would a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist because social workers are a lot cheaper in providing care. The evidence is that they’re no different in terms of the outcome of care.

The most important findings come from global mental health studies in countries like India. Vikram Patel and Paul Farmer have shown that you can train local people who have limited education to deliver psychotherapy, and their outcomes can be indistinguishable from those of psychologists and psychiatrists. That is the future of mental health: that psychotherapy works as effectively as medication. That’s number one. Two, it does not have to be delivered by a psychiatrist or psychologist.

We want PhD psychologists and MD psychiatrists to focus on patients who are recalcitrant to ordinary treatment. These patients require sophistication in the use of medications, psychotherapies, etc. There’s a radical re-visioning of the mental healthcare system—psychiatrists and psychologists will not be the dominating forms of expertise in the future.

The social structures and culture of medicine and psychology are as important as the social structures and culture of patients and families. We’ve never combined them in that way, but now we must; otherwise, we’re facing a disaster.

I wrote about my care for my late wife, who died of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. We’re losing caregiving in the healthcare system, and we are seeing powerful forces in society make it much more difficult even to have care in the American family. This is very gendered, as you know, as a woman. Men like to talk about care, but women actually do it.

Dhar: The medical system is not very efficient. I spent 10 years in the U.S., and one of the primary reasons I moved was the constant existential anxiety of not having healthcare despite having health insurance. Sometimes, the way doctors and patients explain what is happening is different. The doctor might focus on a chemical imbalance, and the patient might say it’s an ancestral course. You wrote about these types of conflicts in how patients and psychiatrists explained their problems. But in today’s world with pervasive social media, things like ADHD and Dissociative Identity Disorder are peddled out as identities. There is a looping effect here of how biomedical narratives are now changing people’s experience of themselves and the way they experience distress. How do we work with people when our illness narratives have shifted so much when a patient might enter the office saying, “I am ADHD”?

Kleinman: It has to do with the development of an educated middle class globally. The middle class has come to understand genetics, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals and is better educated in science and technology. It comes to the physician not just with the illness experience but also with their own views of the disease.

Ideally, this could be a way that physicians and patients can be more collaborative. However, in fact, instead of being more collaborative, it often leads to further tension, where patients will insist on a certain kind of biomedical understanding. The practitioner may disagree with that. For example, the stigma of depression and anxiety has receded so much amongst the global middle class that it’s now possible in China to talk to young people about depression and anxiety. But that doesn’t necessarily always work out for the good.

Patients may insist on a particular diagnosis. They may insist on that diagnosis because it is associated with a medication they want or because they feel that that diagnosis is less stigmatizing than another. Some of this is very good.

I organized a report by the World Bank in 2016 called “Out of the Shadows” about mental health. My idea was to show partly that depression was a very common problem all over the world. On the other hand, it’s equally important to recognize that about 50% of cases of depression do not require any kind of intervention that is professional. They respond to things like a confiding relationship, improving people’s social circumstances, getting a better job, having improvement in a conjugal relationship, dealing with sexual problems, dealing with the environment in which people are working and living, diet, exercise—all those things contribute to half of people with depression getting better. It’s the other half that don’t get better who require the medical interventions.

I’m suggesting that a large number of mental health problems are responsive to improvements in society, families, schools, and workplaces, and those are the kinds of social interventions that are needed. Mental health is not just a medical matter. It has to do with education, the workplace, families, and communities.

Over the next 30 years we’re going to see major efforts to get profit-making out of health and mental healthcare. The mental health domain is foundationally organized on care, not profit. The language required is not an economic language of efficiency but a human language of care. I think that’s going to increasingly lead to change in the future. We should prepare ourselves for changes.

I can point to one very important one. While the most common mental health problems are being destigmatized, that has not happened with psychotic disorders. With schizophrenia and even bipolar, when it produces mania and psychosis, the stigma globally is still strong.

Dhar: Partly, this is because we have traditionally had a very pessimistic outlook towards schizophrenia—there is no coming back. These understandings have been challenged, like Robin Murray’s recent writings. In my work in rural India, the experience of hearing voices was very common, and people were open to talking about it. They had their own understanding of why this would happen. But if I coupled it up with biomedical terminology like “psychosis” and “schizophrenia”, immediately there is fear and stigma.

Kleinman: We have an anthropologist who has done magnificent work in this area, Tanya Luhrmann. (See prior interview with Mad in America.)

Tanya’s work is extraordinarily important. She shows that hearing voices is so common in certain settings that even the term hallucination is the wrong term because hallucination means an abnormality in perception. In the early days of bereavement for a loved one, many people believe they heard the voice of the person who just died or actually saw that person. Those illusions are common enough to be part of the normal experience. What is bereavement anyway? It is about the caring of memories, and you make those memories vivid by hearing voices and by seeing things.

This is the lack of utility of a language of pathology. Where a language of pathology is useful, use it; where it’s not useful, don’t use it. Families with adolescents who are on the spectrum of autism try very hard to normalize that experience. They run up against efforts to medicalize it.

We’ve seen developments in this regard among most First Nation peoples. There are efforts to get rid of the language of pathology because it makes everything look bad, wrong, and broken, and to use more traditional languages that have the possibility for uplifting, reform, and a more positive view of people.

Dhar: Research suggests that in non-western cultures, among ethnic minorities, and also among people from lower socioeconomic sections in the U.S., there is a tendency to have your experiences in the body—somatize your experiences. For e.g., among these groups, depression presents via physical symptoms like backache or burning sensation, but in more affluent or Western societies, it looks like hopelessness and existential dread and the experience is psychological.

My question is: given that we diagnose depression based on how symptoms present, can we even call it depression if the presentation is drastically different? If I use a behavioral checklist to diagnose depression, and the behaviors are completely different in another culture, where is the evidence that there is some underlying true depression, especially in the absence of biological markers?

Kleinman: That’s a terrific point. Human beings have a psychophysiological holism. There’s no separation of mind and body in human experience. When you’re having problems that we call depression or anxiety, you’re having physical symptoms as well as psychological symptoms. What distinguishes societies is not necessarily that somatization is more common in the non-Western world and psychologization is in the Western world, it’s that amongst the educated middle class all over the world, they’re being socialized into a global culture which increasingly is being psychologized, is developing sophistication and depth in the use of psychological terms in reference to their own experience.

If you go from the upper middle class to the working class, you’ll see a difference independent of race and culture that has to do with our forms of education. By the way, that psychological language is not necessarily “right.” It’s picking up on one side of the symptoms, the psychological, but not paying attention to the somatic.

Chronic fatigue syndromes have a long history that gets punctuated by the development of the term neurasthenia in 1869. That term spread all over the world because it suggested that the problem was in the nerves, not in the psyche, and therefore, less stigma was attached to it. But nowadays, as people have become more and more psychologized, that term has gotten thrown out, and people are using psychological terminology. There’s no evidence that if you have depression and use psychological terminology, your outcome will be better than if you have depression and use physical terminology.

You have a psychophysiological experience, and it’s integrated. It’s only the way we think about things that separates that out. Where do those thoughts come from? From the way biomedicine separated out the mind and the body in the past.

Dhar: You’ve talked about the importance of global mental health—the need to take mental health services to Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). One of its proponents, Vikram Patel, has written that some of the problems in these countries are 1) primary care physicians don’t recognize common mental disorders, 2) enough screening is not done in primary care settings, and 3) there isn’t adequate treatment, both antidepressants and psychosocial treatment.

But in the global north itself, there are emerging concerns about all of these things. For example, Allen Frances has repeatedly attributed overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis to primary care settings. Screening instruments are under scrutiny for multiple reasons, such as leading to overdiagnosis, not producing good outcomes for patients, and being developed by pharmaceutical companies that gain from overdiagnosis. Regarding treatments, you have yourself written that psycho-pharmaceuticals have been found to be a lot less effective and have severe adverse effects.

First, why should we introduce things we are already beginning to critique and problematize in the U.S., the UK, and Canada into the Global South?

Second, at an international conference recently, I found many psychiatrists talking about structural determinants of mental health, such as poverty, violence, etc., and the importance of access to care for people in poorer countries. But when I asked, “What care?” a speaker mumbled something about antidepressants. How is farmer suicide, which is caused by predatory money lending policies, neoliberalism, etc., treated by antidepressants? My worry is that the global mental health movement, despite its promises of paying attention to context and systems, is getting co-opted.

Kleinman: They will get co-opted. That’s probably the most important word that you used because the political economy of healthcare is part of the problem—a big part as you’ve identified.

Aging citizens of Japan, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden, and Norway have access to home health aides. In the United States, very few people do because we don’t have long-term care insurance.

There is an attempt by the Chinese to provide the rural poor elderly with long-term care insurance. Insurance for mental health care generally is extremely important. Vikram Patel’s work is appropriate for the United States too, not just Goa. Some states are using community healthcare workers to follow up on just the questions that you raised.

However, I do think that one size doesn’t fit all. In China, one problem is that the primary care system is not functioning. Having a functional primary care system will be a game-changer for the mental healthcare system, but it will have problems, probably the overuse and misuse of antidepressants, etc.

But I think you said it beautifully. The idea that the West has the answers and the rest get the solutions from the West—that’s gone for good. That’s part of the colonization of the mind.

We engage with China and India as equals; we’re all in this together. A solution in India may be a solution in the United States. I don’t want to see the names of Western researchers as authors of papers on global mental health because that is still colonization. I want to see the names of our Indian, Chinese, and African colleagues. I want to see a much more collaborative kind of care.

***

MIA Reports are made possible by donations from MIA readers like you. To donate, visit: https://www.madinamerica.com/

“We have at least eight studies that show that if you compare first-year and fourth-year medical students’ interviewing skills, in paying attention to the person and the social context, first-year medical students are actually better. This is deeply disturbing.

NO SHIT. This is the reason why medical doctors should GET THE FUCK OUT of the ‘mental health’ business.

Any idiot intuitively knows that emotional problems are different from physical ones, even though emotional problems sometimes manifest physically (and sometimes vice versa) which makes seeing an M.D. the LAST thing ANYONE should do —

Report comment

CLARIFICATION: …seeing an MD should be the LAST THING on anyone’s list when feeling EMOTIONALLY DISTRESSED —

Report comment

“Psychiatrists have been turned into prescribers of medication. That is the role that the healthcare system forces them into. Healthcare insurers would much rather pay social workers to do psychotherapy than they would a clinical psychologist or a psychiatrist because social workers are a lot cheaper in providing care.”

There you have it, folks, psychiatry’s typical cop out answer! They continually blame everyone BUT themselves for the situation they find themselves in while REFUSING TO ADMIT that THEY ALONE write the crap-happy DSM, THE VERY THING health insurers rely on to keep the money rolling in for psychiatry and its offshoots!

It seems odd that a medical anthropologist neglects to directly mention the DSM, the symbol of modern psychiatry. Nor does he mention forced treatment! Were these deliberate oversights? Perhaps. But evading issues comes naturally to people continually seeking to dodge the bullet.

Report comment

CLARIFICATION: Psychiatry REFUSES TO ACKNOWLEDGE that THEY ALONE write their crap-happy DSM, which is the FOUNDATION their crap-happy ‘profession’ —-

Report comment

This podcast is about context. But Kleinman didn’t say much of anything about the fact that psychiatrists are trained in a medical context, that the DSM is written by psychiatrists, that medical doctors are the ones (over)prescribing psychiatric drugs, something that usually happens WITHOUT INFORMED CONSENT.

Looks pretty contextual to me.

Report comment

It seems anthropologically inappropriate to not have discussed following:

1. Psychiatry’s stigma-enhancing DSM

2. Psychiatry’s lax attitude regarding informed consent

3. Psychiatry’s ‘medications’ causing debilitating iatrogenic harm/protracted withdrawal

4. Psychiatry’s continual use of coercive practices such as involuntary hospitalization and/or drugging

5. Psychiatry’s excessive use of ‘drug treatments’ causing the exponential increase in ‘mental health’ disability claims

6. Psychiatry’s role in guardianship abuse

Softball interviews like this one are the reason psychiatry KEEPS GETTING AWAY with peddling its garbage.

I expect better from MIA.

Report comment

“…about 50% of cases of depression do not require any kind of intervention that is professional…. It’s the other half that don’t get better who require the medical intervention.”

50%? I don’t agree with that at all. I don’t think it’s anywhere near 50%.

There’s no way to determine the best thing to do when it comes to relieving psychic distress. But caution is rarely used when it comes to ‘medicating’ people, which is problematic since psychiatric ‘medications’ ARE KNOWN to significantly aggravate problems in the long run—which is something most medical professionals REFUSE TO ACKNOWLEDGE as this makes them question what they’ve been taught, which in turn makes them question themselves, which is the opposite of what they’re trained to do! So their flawed reasoning usually goes like this: “Well, if someone ends up in my office, that must mean my services are necessary because in the end medicine knows all the answers!”

But that’s turning out not to be the case, as many people are finding out ON THEIR OWN.

Report comment

“It’s the other half that don’t get better who need the medical intervention.”

That’s a disturbingly even-handed statement.

A word to the wise: Politics has no place in medicine.

Report comment

Saying that half the people suffering from depression need “medical intervention” is an unreasonably high number. But I bet it’s one that’ll keep the folks in Big Pharma happy!

Report comment

Question: So why are half the people with “depression” getting medical intervention THEY DON’T NEED???

Report comment

7. Psychiatry CARELESSLY poly-drugging people into oblivion WITHOUT A SECOND THOUGHT —

8. Psychiatry playing on people’s fears and insecurities through direct-to-consumer advertising for so-called ‘medications’.

Care and context have been thrown out the window.

Report comment

[Comment by moderator: I removed this paragraph].

By far one of the most awful experiences of my life was seeing a psychiatrist who right off the bat judged me negatively because I hadn’t yet achieved certain ‘milestones’ like marriage and full-time career at the advanced age of 24! He paid no attention to the fact that I had recently survived a devastating auto accident. He had no curiosity of the life I’d led so far nor the things I had achieved up to that point which would have informed him of the things I valued.

It was easy to see the guy was fixated on outward forms of achievement, which was very disappointing, but I chalked it up to his own impatience and insecurities at finding himself few years older than most doctors fresh out of residency. I also sensed he secretly resented me for not living a life he could understand. I sensed he was unaware of his own immaturity.

Dynamics like this are impossible to eliminate, no matter the care or context.

Report comment

CLARIFICATION: It was easy to see the guy was fixated on CONVENTIONAL forms of accomplishment, that he viewed conventional forms of accomplishment (a college degree, a full-time job, a serious relationship) as ‘signs’ of someone’s ‘mental health’. He seemed to have almost no imagination or psychological flexibility, that he had trouble understanding a creative personality.

And get this: one day the asshole went so far as to say my “track record wasn’t that good” which proved to me he was an even bigger son of a bitch than I’d suspected from the beginning.

Report comment

Correction: I also sensed he secretly resented me for my not being someone HE COULD RELATE TO.

Which I consider not merely his personal failing, but also an indictment of the ‘mental health’ system as a whole.

Report comment

“We want PhD psychologists and MD psychiatrists to focus on patients who are recalcitrant to ordinary treatment.”

Using words like ‘recalcitrant’ sounds like a veiled reference to the thorny subject of FORCED TREATMENT.

But whitewashing doesn’t change the nature of an inherently abusive practice with a long and continuing history of racism, sexism, and the usually unspoken REALITY of classism.

“These patients require sophistication in the use of medications, psychotherapies, etc.”

Psychiatric prescribing is guesswork; there’s nothing ‘sophisticated’ about it; no one should be forced to ingest ‘medication’ of any kind.

The same goes for ‘psychotherapy’; no one should be forced to interact with anyone stupid enough to think they have all the answers.

Report comment

“Vikram Patel and Paul Farmer have shown that you can train local people who have limited education to deliver psychotherapy, and their outcomes can be indistinguishable from those of psychologists or psychiatrists. That is the future of mental health: that psychotherapy works as effectively as medication. That’s number one. Two, it does not have to be delivered by a psychiatrist or psychologist.”

This doesn’t surprise me. In my experience, the higher the degree, the less likely it is for someone to be able to relate to people having a hard time, and (strangely enough) this applies more often in my personal experience to people with degrees in ‘mental health’!

Common sense says: Seek out people who’ve not only been there, but people whose egos aren’t too big to admit it.

Report comment

Psychiatrists are trained in a medical school.

Psychiatrists write the DSM.

MD’s write prescriptions for psychiatric drugs.

But since (most) emotional problems aren’t caused by physiological problems, why seek help from a physician???

Wrong context leads to wrong care.

Report comment